The Salute Difference: Beyond "Good Enough"

Article Navigation

Mil-Spec Basics

The Salute Approach

Coat Construction and Interlinings

Chest Pieces

Full Canvas Construction

Button Area Support

Canvas Sleeve Inserts

Detachable Buttons

Sleeve-End Reinforcement

Enhanced Pocket Lining

Improved Sweat Shield

A Commitment to Innovation

At The Salute Uniforms, we're constantly exploring ways to deliver dress uniforms with the level of quality that the members of our nation's armed forces expect and deserve.

For decades, manufacturers of uniforms for the United States Armed Forces have had to meet strict material and design requirements in their production processes. Commonly referred to as “Mil-Spec,” these standards were established for two obvious reasons. The first is to ensure that uniforms are, well, uniform, as in the Merriam-Webster definition: “having always the same form, manner, or degree: not varying or variable.” The second is to guarantee a baseline for quality and appropriateness. For example, manufacturers can’t substitute a similar-looking but cheaper, less-durable fabric in order to boost their profits, no matter how closely it resembles the Mil-Spec version.

Unfortunately, the nature of government acquisition programs means that uniform manufacturers consider Mil-Spec standards as lofty goals to be achieved rather than the starting point in crafting the highest-quality uniform at a competitive price.

Mil-Spec Basics

When a government entity contracts with a manufacturer for military uniforms, it agrees to pay a set price for garments it will sell in military exchanges such as AAFES and NEXCOM. Because the manufacturer’s compensation is fixed, any costs to the manufacturer associated with improvements beyond the Mil-Spec standards will come directly out of its bottom line.

For a manufacturer producing issue dress uniforms—the ones all new enlistees receive for free—a simple design enhancement that costs, say, 50 cents per uniform spells a loss of tens of thousands in revenue. That might not sound like a lot in the scheme of things, but keep in mind that these manufacturers won those contracts by submitting the lowest bid, so their profit margins are likely quite slim to begin with.

Of course, military personnel can turn to commercial sources outside AAFES and NEXCOM to purchase their dress uniforms. Since these manufacturers are selling directly to the consumer, they have the opportunity to deliver garments that exceed Mil-Spec and still charge competitive prices (beating exchange prices is nearly impossible due to the volume those organizations order). Indeed, it only makes sense for these retailers to explore improvements as a way of making their brand stand out, especially in light of the fact they’re competing against both the exchanges and other non-exchange sources.

But there’s something these commercial sources don’t want you to know: They aren’t the ones actually manufacturing the uniforms. Typically, they are contracting with the same manufacturers supplying AAFES and NEXCOM—manufacturers unlikely to retool their high-volume production lines to incorporate design improvements even if the retailer upped the price it was willing to pay. And sometimes supply-and-demand exigencies or other business factors force a retailer to source its inventory from a manufacturer other than the one it’s traditionally used, which in turn raises the issue of product consistency.

In either case, almost all of these vendors are really just middlemen selling uniforms that, like the ones found in the exchanges, simply meet the “good enough” standards of Mil-Spec.

Return to Navigation

The Salute Difference

At The Salute Uniforms, we’ve taken a different approach.

As the only commercial-source vendor of Mil-Spec uniforms that manufactures the items we offer, we have complete control over every single step of the production process. When you order a uniform from us, it’s shipped directly from our factory: There is no middleman. This level of oversight allows us to innovate in ways that aren’t viable for manufacturers limited by the constraints of fixed-price contracts and simply aren’t available to the vendors ordering from them.

After listening to our customers’ feedback on the shortcomings of Mil-Spec designs, we decided to go the extra mile to manufacture uniforms with unique, value-added features, utilizing premium components whenever possible while keeping our prices highly competitive. As a result, about the only similarity between our uniforms and the ones you’ll find inside AAFES and NEXCOM stores is that they meet the appropriate minimum standards for design and materials.

One of the areas where we saw many opportunities to improve upon the Mil-Spec minimum design requirements was in coats. Coats are the most distinct part of a dress uniform, but they’re also the most complicated, assembled from numerous sections made from a variety of materials. We took this complexity as an opportunity to closely examine how we could upgrade individual coat components and the ways in which they’re assembled.

Some of these enhancements were inspired by customer comments, while others sprang from brainstorming sessions involving our sewers, patternmakers, and even our CEO. Here are a few of the most notable examples of the materials and concepts that make our coats unmatched when it comes to quality and value.

The Inside Scoop

All dress uniform coats are crafted from the same specified materials, so they tend to look the same at first blush regardless of manufacturer. But when it comes to comfort, fit, and durability, it’s often the things you can’t see that matter the most—and just how high a coat ranks in those categories depends largely on what type of construction was used to manufacture it. To fully appreciate the differences in construction types and why they matter, a basic rundown on suit materials and components and how they’re put together is necessary.

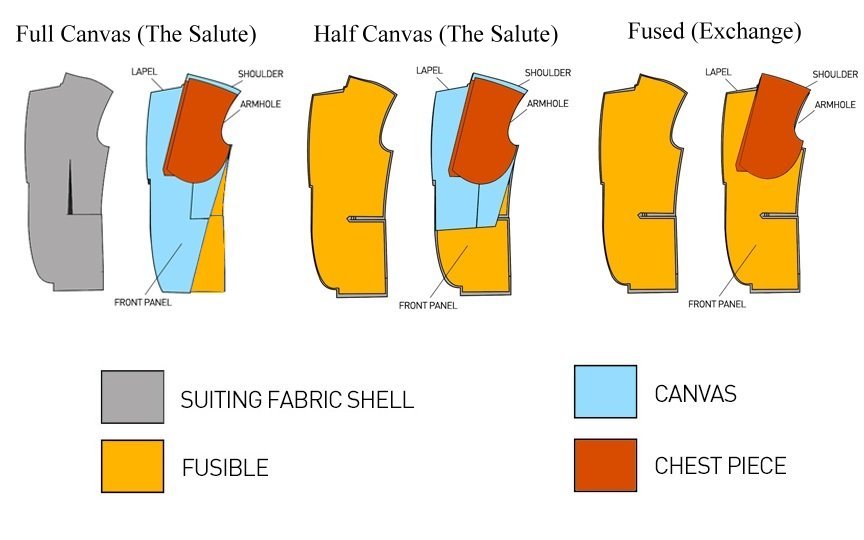

The main things that jump out at people when they see a suit coat are the outer fabric and the inner lining material. What they don’t see is the

interlining—the material inserted between the outer shell and the lining to help the coat maintain its shape. Interlining comes in several varieties of fabrics, both woven and non-woven; when it comes with an adhesive substance on one side that allows it to be fused to another piece of fabric through heat treatment, it’s called a

fusible.

Another material that’s used in the manufacturing of suit coats is a sturdy fabric made of horsehair, commonly referred to as

canvas. Canvas is used in areas of a suit where extra support is needed and is produced in varying degrees of stiffness and strength.

Also between the lining and the outer material is the

chest piece, a section that covers the chest area (duh) horizontally from the armholes to the hem and vertically from the collarbone to below the pectorals. The chest piece is made of canvas and is usually covered by felt on one side. The section of the suit comprising the area from the shoulders and lapels down to the bottom of the coat is called the

front panel (it does not extend out to the side of the coat).

Now that you’re acquainted with the basic terms, here’s a diagram that shows the different types of suit construction.

|

| Images originally by Black Lapel, modified to reflect The Salute Uniforms' designs. Original images and article here. |

The Mil-Spec for dress uniform coats is a fused construction with a chest piece, like you see above on the far right. We’ll go into more detail about how our full-canvas construction compares to the fused construction of other manufacturer’s coats, but for now let’s talk about one of the most important but unseen parts of your coat—the chest piece.

Return to Navigation

Heavy Medals

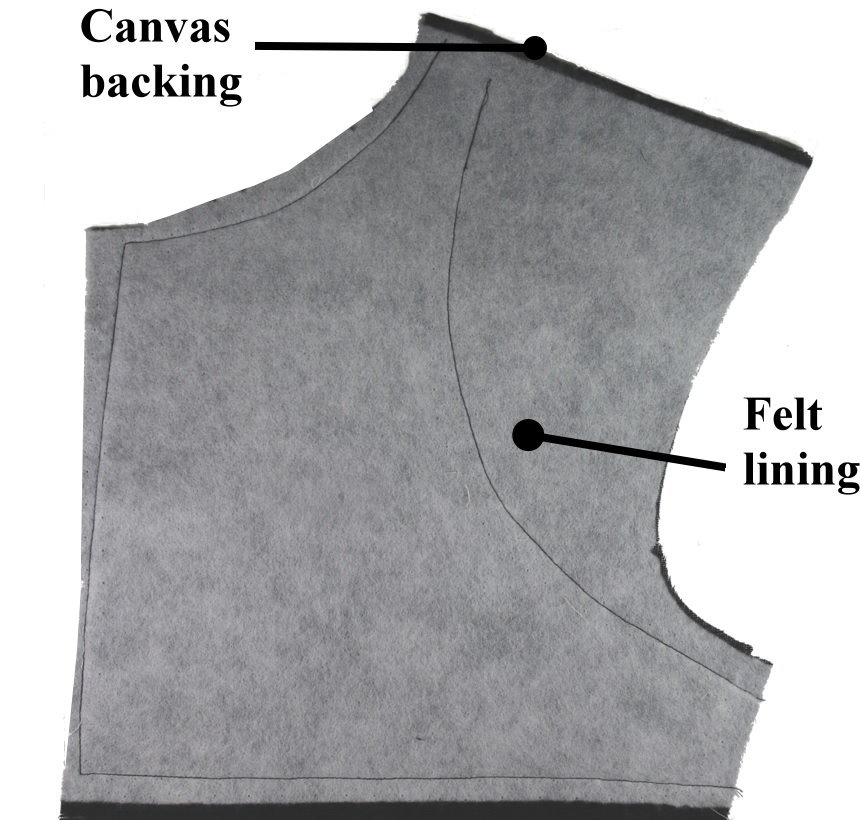

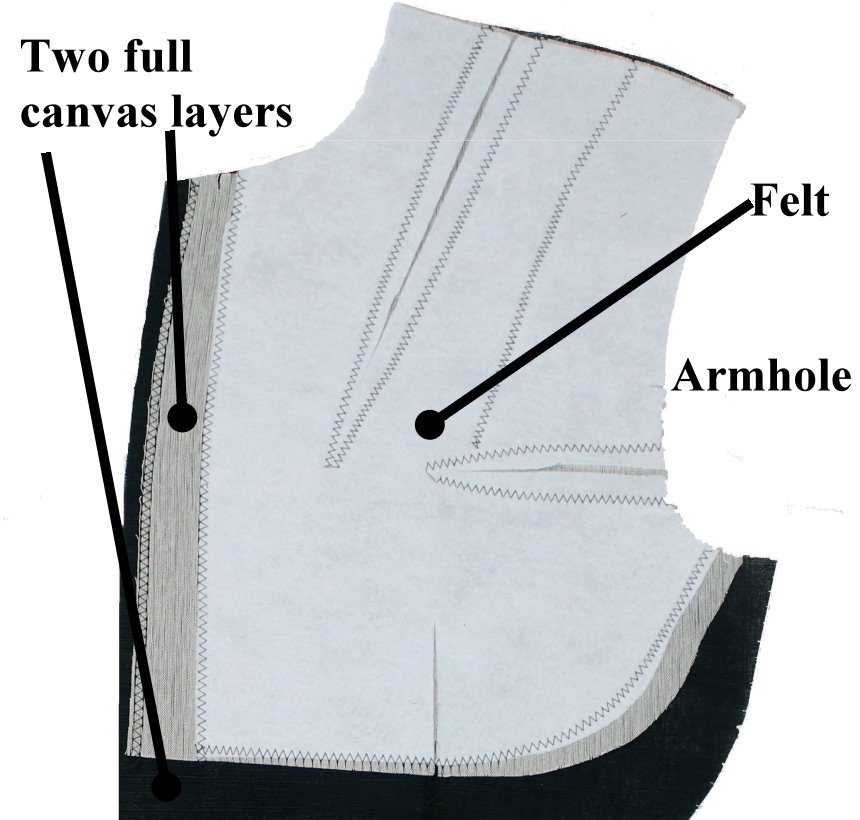

Chest pieces are mandated in the Mil-Specs for all for dress uniforms, and the reason why can be summed up in one word: medals. Even a couple of medals can exert considerable downward pull on the front of the coat, but unfortunately the Mil-Spec for chest pieces is hardly more than an acknowledgement that a chest piece is necessary. It calls for two layers of canvas, one covering the entire chest piece coupled with a smaller piece shaped like an inverted apostrophe running from the shoulder to the underarm area. Both layers are made from the same grade of canvas, which isn’t particularly strong as far as canvas goes. The side of the chest piece against the lining is covered in felt.

Just how inadequate is the level of reinforcement provided by chest pieces made merely to Mil-Spec? We’ll put it this way: when we began hearing reports of service members resorting to use a cardboard backstop to augment the chest piece and lessen the strain on the front of the coat, we knew this was an area where we could deliver some much-needed improvement.

|  |

| Chest piece exterior, Exchange coat | Chest piece exterior, Salute Uniforms coat |

For our chest pieces, we use two layers of canvas that cover its entire area. What’s more, the second layer is a much sturdier (and costlier) type of canvas that provides outstanding support for even the most decorated warfighter’s medals. This second, stronger layer of canvas faces the inside of the coat, so we cover it with felt to prevent it from damaging the more delicate lining material.

|  |

| Chest piece interior, Exchange coat | Chest piece interior, Salute Uniforms coat |

Return to Navigation

Fitting and Proper

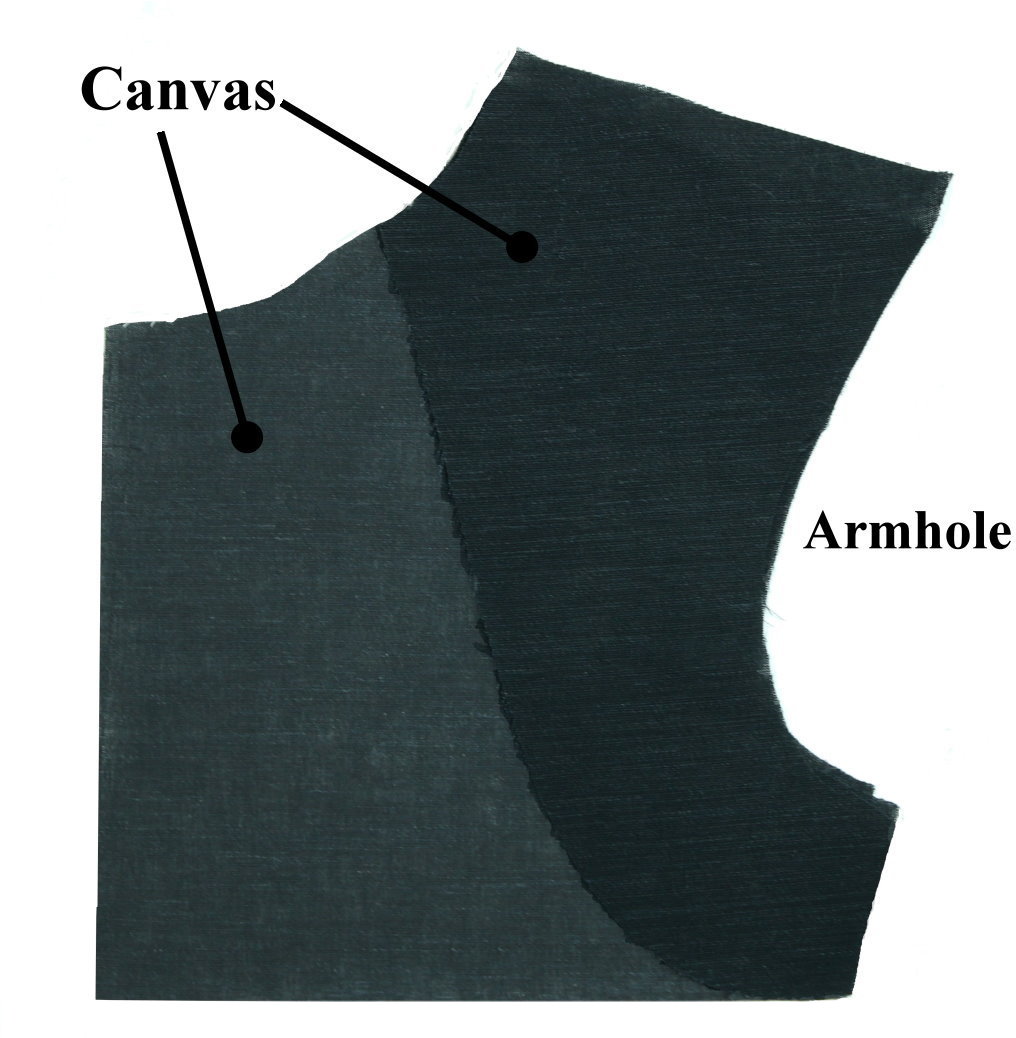

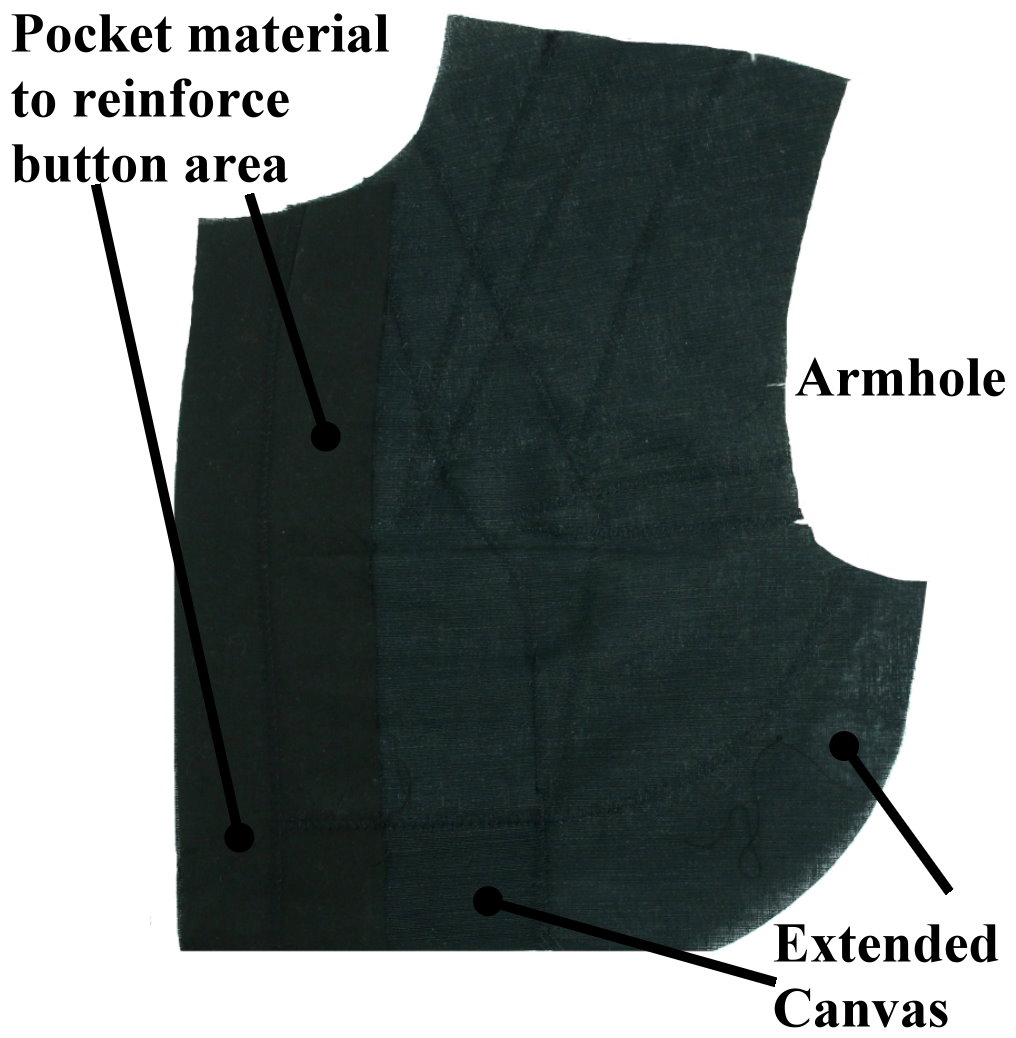

As you can see in the diagram above, the only place you’ll find canvas in one of our competitors’ coats is the chest piece. That means the only support for the coat’s outer fabric is fusible material that’s been glued to it, and some Mil-Specs don’t even call for fusible all the way to the bottom hem. You might think that that just a piece of fusible would make the coat limp, but instead it makes it unnaturally stiff.

Before fusibles were introduced, tailors used canvas to provide support for the coat’s outer fabric, but today it’s found only in higher-end suits. The advantage of canvas is that because it’s somewhat loosely attached, it “floats” with your body’s movements. Over time, it begins to conform to your body’s shape while simultaneously acting as the coat’s “skeleton.” Full-canvas or even half-canvas construction is more expensive than fused due to the added cost of the canvas and the labor to sew it properly.

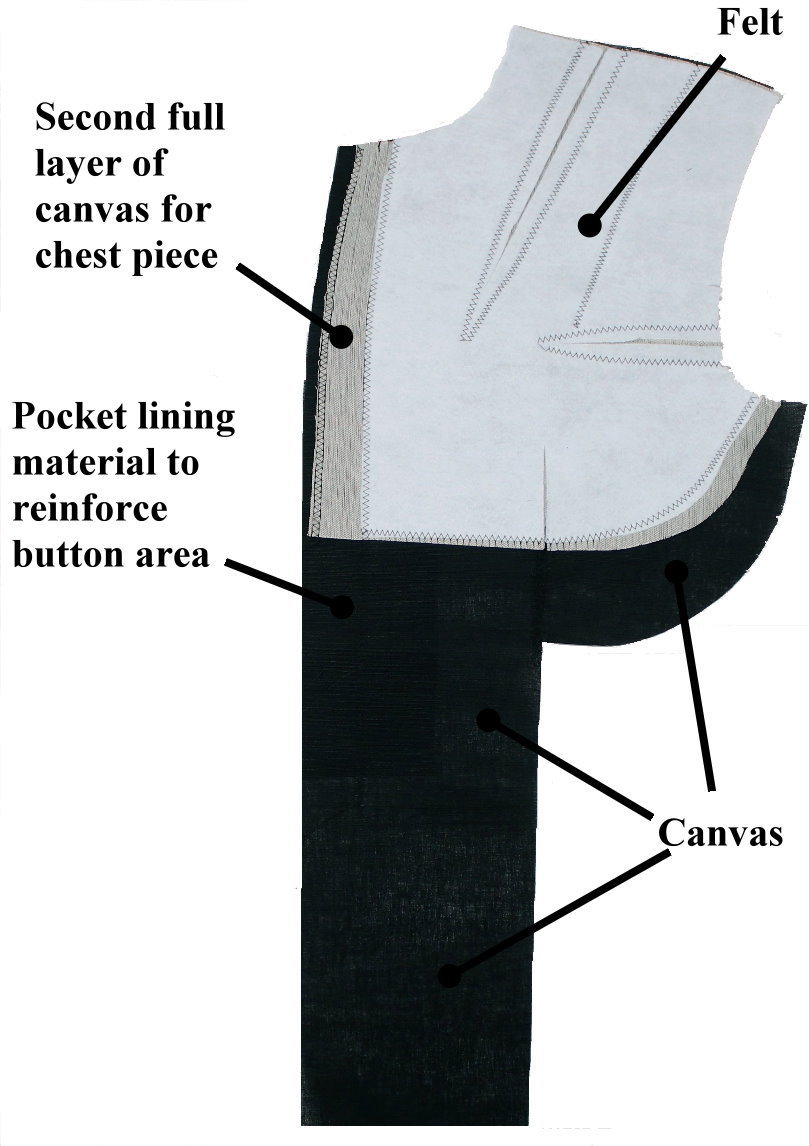

|

| All dresss uniform coats from The Salute Uniforms feature a full-canvas front panel with button areas reinforced with sturdy pocketing material. |

We use a full-canvas construction for all our service coats, along with fusible material in the bottom front part of the coat called the “skirt.” (We can't use canvas in the lapels of our Mess Dress coats because it would be visible due to the thin, delicate satin called for in the design.) In both cases, the result is a coat that fits and drapes much more naturally than one made with a fused consturction, which fights your body’s movements as it tries to conform to the coat’s outer shell. Another advantage of coats made with full-canvas construction advantage is that they have a longer wear life, and during that time they maintain their crisp appearance even after multiple trips to the dry cleaners. They’re also not prone to “bubbling” caused by air pockets that can be created when the fusible comes unglued from the coat’s outer fabric; the more fusible used in a coat, the more places it can separate.

If you’re still not convinced at the superiority of full-canvas or half-canvas construction versus fused, just Google “full-canvas suit” sometime (be prepared for plenty of images of well-heeled hipsters, though).

|

| A wide strip of strong pocketing material is used to reinforce button areas on the front of the coat. |

But we don’t stop there.

No part of a dress uniform coat gets a workout like the button areas—they’re the only parts you pull and tug on every time you put it on or take it off. To prevent them from bending or losing their sharp lines, we place a strip of stout pocketing material on top of the canvas already in place there. It’s just one more way we seek to ensure you look your best for the longest time possible in your dress uniform.

Return to Navigation

Shouldering the Load

Padding has been used to varying degrees in the shoulders of suit coats for decades, and military dress uniforms are no exception. Besides creating a professional, squared-away look, padding also frequently serves to strengthen the shoulders of uniform coats that have epaulets or heavy braiding.

But if you simply attach a sleeve to the armhole of a suit with a padded shoulder, the lack of support where the two are joined can cause the sleeve to noticeably sag and even fold inward. Instead of a full, gently sloping transition from the shoulder to the top of the sleeve, you get an effect not dissimilar to what you see with a linen extending over the corners of a table.

Not professional.

|  |

| Coat sleeve without canvas reinforcement (Exchange) | The Salute Unforms' coat sleeve featuring canvas reinforecement |

To address this issue, we employ a technique similar to the one we used for the coat’s chest piece and front panel. In this case, we sew together two roughly oval-shaped pieces of canvas and insert it between the lining and the outer fabric of the sleeve before we attach it to the armhole. Following the shape of your body yet providing support for the outer fabric, this canvas sleeve reinforcement drastically reduces any sagging or folds by eliminating the drop-off effect you get if you simply attach the sleeves to the stiff shoulder pads.

Return to Navigation

Button, Button

Dry cleaning is an unavoidable, recurring expense associated with owning a dress uniform, but paying extra to have coat buttons removed to avoid damage from harsh chemicals doesn’t have to be. And no, we’re not talking about removing them yourself and then re-sewing them after you’ve picked up your freshly pressed suit.

Removable suit coat buttons have been around for some time; in the Marines, for instance, having the Dress Blue coat “buttonholed” to accept removable buttons was something of a tradition. We decided to incorporate it whenever possible in the design of all of our dress uniform coats after some of our customers mentioned this to us, saving service members the cost of implementing this common-sense upgrade.

With our dress uniforms, removing and reattaching buttons is as easy as putting a key on a keyring—great for those dry-cleaning visits or when you need to replace a lost or damaged button (or if you choose to replace the issue buttons with approved premium versions).

|

| Besides offering easy removal for dry-cleaning visits, our removable buttons also hide the button shank behind your coat's lining. |

The value of removable buttons is not lost on all uniform vendors. An approach taken by one company is to ship their coats with a “button strip”—a rectangular swatch of outer-shell suit fabric, buttonholed to accept removable buttons, that’s sewn onto the button-side of the coat. Besides allowing simple button removal, a purported advantage of the button strip is that it can be removed and repositioned to accommodate weight gain.

We considered this technique, but settled on our current design after our Master Tailor pointed out some drawbacks to this system. Ironically, one of them is directly related to dry cleaning, the primary reason for incorporating removable buttons in the first place. You see, after several dry cleanings, the outer suit fabric fades ever so slightly—except under the button strip. Move the button strip inward, and the area where it had been previously sewn on will be darker than the rest of the coat.

Another disadvantage of the button-strip system is how it affects the coat’s lapels. Buttons are carefully positioned so that the lapels cross at a precise point when the coat is closed. Moving the buttons changes the symmetry of the lapels; someone might not be able to tell you precisely what looks wrong about the way the coat fits when it’s buttoned, but they’ll know it doesn’t look right.

Finally, button strips are only applicable to the buttons that close the coat—but dress uniforms have buttons all over the place. We use removable buttons whenever we can for pockets, sleeves, and epaulets.

A Stitch in Time

Members of the military might not wear their hearts on their sleeves, but sometimes it seems like everything else is fair game (with the exception of United States Air Force dress uniforms, that is). Chevrons, service stripes, ornamentation, buttons, and more can all be found to varying degrees on the sleeves of dress uniforms—and the uniform regulations for each of the service branches is very specific about where and how they’re attached. Regulations also spell out how sleeves are supposed to fit on a wearer’s arm: A sleeve that stops at the wrist or extends to the knuckles isn’t going to get the wearer a thumbs-up and a slap on the back during inspection. That’s why we ship all our dress uniform coats with sleeves that not only are unfinished, but also longer than most customers need.

Those unfamiliar with the intricacies of sleeve regulations and the placement of various devices and insignias might think they’re getting shortchanged by receiving coats with sleeves that haven’t been hemmed. But there are plenty of other, less noticeable ways we can have skimped in order to save money and haven’t done. And the fact of the matter is that, in the vast majority of cases, unfinished sleeves actually lower alteration costs while guaranteeing the best possible fit.

You see, while uniform retailers can assure you of a fairly good fit in terms of coat girth and length, the wild card in the equation is arm length—which means just about everyone who buys a coat will need to have the sleeves altered for the proper fit. If we shipped our coats with finished sleeves—i.e., hemmed and with service stripes and other insignia already sewn on—a lot of our customers would end up paying to have those items removed and then resewn after the sleeve has been altered to the right length.

We make the sleeves longer than you might expect for the simple reason that it’s a lot easier to shorten sleeves that are too long than to lengthen sleeves that are too short. And while it’s possible to let out a sleeve that’s too short, the line marking where the sleeve originally ended will be visible for quite a while afterwards because it received an industrial-strength pressing at the factory. That can’t happen when you start with unfinished sleeves.

The issue of sleeve length brings up another enhancement: wigan reinforcement. Sleeve ends are in constant contact with your environment and can tend to weaken and even fray with repeated wearing and dry cleanings. Most of our competitors are aware of this issue because many of them will use a strip of fusible at the end of the sleeve in an attempt to strengthen it. Just as with the inadequate chest piece, however, this is more of a nod to the fact that the sleeve end needs reinforcement rather than an effective method of addressing the problem. For one thing, fusible doesn’t offer very much support for the sleeve end. And because the fusible is literally glued onto the suit fabric, these strips are cut and tossed away whenever a sleeve is shortened.

.jpg) | .jpg) |

| Coat sleeve with fusible strip for reinforcement (Exchange) | Coat sleeve reinforced with easily detached wigan (The Salute Uniforms) |

On our uniforms, on the other hand, you’ll find a wide piece of material called wigan at the end of each unfinished sleeve. We attach this strong fabric, similar to canvas, by sewing it loosely onto the end of the sleeve, making it simple to remove during the alteration process and reattach once the proper length has been determined.

Wigan costs quite a bit more than fusible and, like canvas, requires some additional labor, but the value it adds to each coat is indisputable.

Return to Navigation

.jpg) |

| All our jacets feature interior breast pockets reinforced with fusible material. |

Pocket Change

Whether it was done as a sartorial prerogative or as a cost-saving measure, the specs for many military coats don’t call for true outside pockets. (We tend to think it was the latter since some of them have faux pockets.) Whatever the reason, the specs are what they are, and we’re not at liberty to add real pockets no matter how good of an idea we or our customers think it would be.

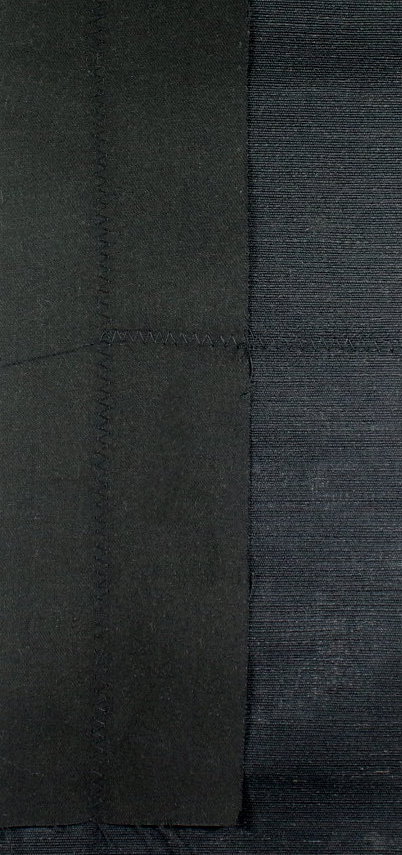

The upshot is that many military personnel use the inside breast pockets on their coats to store their cell phones, wallets, money clips, and sundry other items. When we manufactured our first coats to Mil-Spec several years ago, our customers told us that the tops of these pockets tended to fray as a result of reaching into them for these items, a problem only made worse as people began to use cell phones more frequently (a 2019 study by global tech care company Asurion reported Americans check their cell phones 96 times a day, a twenty percent increase from just two years earlier).

Our solution was to go beyond Mil-Spec and reinforce the pocket’s edge with fusible material. This involves additional labor and material costs, but the result is a considerably more durable pocket that still has a soft, gentle interior. If you’re wondering why other manufacturers took no steps to fix this readily identifiable problem, the answer is simple—they didn’t have to, so they didn’t.

Return to Navigation

Sweating the Details

One of the features mandated in the design of some dress uniform coats is a “sweat shield,” ostensibly included to prevent sweat from staining the outer fabric in the underarm area. Depending on the uniform, it’s usually made of a single layer of suit fabric or lining material. While the inclusion of a sweat shield in the specifications is thoughtful, a thin strip of material is an afterthought. For coats where the specifications call for a sweat shield, we use a thicker fusible that absorbs more moisture than the material found in our competitors’ uniforms.

However, keep in mind that some people perspire at prodigious rates. There’s certainly no shame in that, particularly for those suffering from hyperhidrosis, but we mention it only because in some instances even our enhanced sweat shield might not completely prevent perspiration from reaching the fusible interlining and then the outer fabric.

A Commitment to Innovation

We appreciate not only the need for Mil-Spec standards, but also the challenge of crafting to them. Settling on minimum standards of materials and workmanship is not as simple as it sounds. On one hand, you must keep the cost of the finished product within reason, but on the other you realize that the end product will be worn by men and women who have devoted themselves to the service of their country—and in many instances put themselves in harm’s way in doing so.

That realization, however, doesn’t change the fact that Mil-Specs are

minimums. Some aspects, such as the pattern or suit fabric, are inviolable, so we don’t even need to ponder how they might be improved upon. So we look at other, less-visible aspects of a uniform’s design to see how we can enhance it. We might realize there’s a way to make the garment easier to care for, or perhaps we notice a minor change that will make it more comfortable.

In any event, we have our custom pattern-makers incorporate the change into a sample garment to determine how much it will add to the coat’s cost, then weigh that against the benefit it provides to the person paying for it—

you. And when you take the time to compare our coats against those of any of our competitors, we think you’ll agree that the improvements we’ve implemented for our dress uniform coats make them unrivaled in both their quality and value.